There was a thread not all that long ago on the RADCAT listserv asking people how they got involved in what seems to now be called “radical cataloging,” i.e., basically, anything that questions or deviates from the proscribed traditional standards. Many people cited Sandy Berman as an influence, but I confess I hadn’t even heard of him until I was almost done with graduate school. (I may have even first learned about him on that very listserv.)

Apparently I’ve always been a radical cataloger, because I started deviating from the rules in the very first lecture of my very first cataloging class. It was my second semester in library school, but I had been working at the library where I am now for almost a year at that point, and I had already spent 5 years working for a large retail bookstore chain. The professor was introducing areas of bibliographic description with an exercise where he held up a book and asked students to suggest characteristics that might be beneficial to include in a bibliographic record. Everyone named the obvious components like title, author, etc., right away. The book was green, and I remember him asking the class if we thought that was important enough to be included. I (and several other people) answered yes, and were corrected by the instructor and told that it wasn’t.*

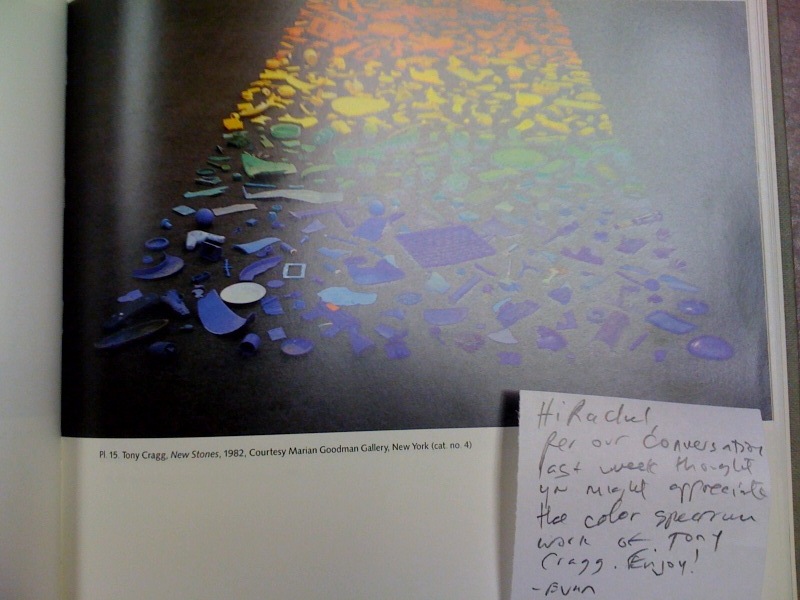

But all I could think about were all the years I spent helping people looking for “that book with the yellow cover” (both in the bookstore and in the arts-oriented library where I work) and how that cover color was information that people wanted to know and wanted to use to find their books, and if that information wasn’t included, we were doing a disservice to a certain percentage of searchers.

So why isn’t cover color included in bibliographic description? I can certainly see obvious reasons why it’s not: covers can vary depending on printing, covers may be multicolored and difficult to describe, books are rebound, the information in the resource and not the resource itself is what’s important, etc. I think these are all certainly valid reasons for excluding color from bibliographic description; the issues and troubles that come from documenting cover color certainly outweigh any benefits derived from including cover description, at least in most libraries.

But in some libraries, like arts-focused libraries, patrons are interested to know what covers look like. This is documented by research as well as my personal observations. So why isn’t color cover included in bibliographic description if it does, in fact, serve patrons?

Because it didn’t fit on a catalog card.

The current cataloging practices we have now evolved directly from the use of cards, specifically card catalogs. I’ve heard Diane Hillman talk about how the semantic web is going to further FRBR and move us away from our archaic self-imposed card-based standards. I’ve watched Tim Spalding’s talk about the limitations of standards based on physical cards. We use “main entry” and the “rule of three” because catalog cards did not have space to include every author/contributor. LC prescribes 3 subject headings because any more would tax the available space on a 3×5 card. Modern cataloging has been far too heavily influenced by what kinds of information we could cram into a two-dimensional space a little less than 15 square inches.

Once we were no longer limited to that tiny piece of cardstock, did we start including more information? Has cataloging changed significantly with the new technologies that have manifested between the typewriter and today? It certainly doesn’t seem like it. I know I’ve talked before about discarding these limitations now that we have technology that’s not held bound by these constraints: why not make the title field repeatable, so that multiple versions of a title can be included in a bib record? Why not list all the authors, instead of just the first three? But it leads me to wonder–what else we might include once we’re no longer held back by the tradition of the catalog cards? People claim that RDA will address these issues, but I see RDA as another piece atop the house of catalog cards, teetering precariously, still based on preceding rules and standards and subject to implementation challenges too.

What I would really like to do is sit down and start from scratch. Pretend like card catalogs never existed. If I walked into my library today, with its users and its collection, but without any previous cataloging, how would I organize it? Would I make a card catalog? An online database? An index? A paper list? Piles? Would the height of the book be important? The page count? Would it be enough for my patrons to simply indicate “ill.” or would I describe resources more specifically in terms of maps, sketches, charts, photographs, images, reproductions, etc.? I might include width, rather than (or in addition to) height, so as to be easily able to calculate the linear feet necessary in our increasingly cramped shelf space. I might list all the authors, not just the first three named or the “main” one. I might include categories for artists, illustrators, designers, models, and other contributors that aren’t authors but are certainly creators or co-creators of the work. I might do a lot of things differently if I was given the chance to start fresh and not required to work under the shackles of a system that not only does not serve my niche library, but cripples the evolution of other libraries as well.

Of course, we can’t start fresh—libraries already have large amounts of time, money, and inertia invested in the defunct status quo. Libraries balk at the effort to perform retrospective cataloging and reclassification projects—to throw everything out and develop new cataloging from scratch would be unthinkable. And truth be told, not only is it economically unviable and incredibly taxing to an already overworked personnel, there’s also oodles of valuable data already in catalogs that would be inefficient to simply throw away.

We can certainly harvest that data, but we need to add all the other stuff that’s missing—all the stuff that was left off in the past because it didn’t fit on that tiny little card, all the additional authors and contributors and series and width measurements and whatever else proves to be important to us and our patrons. LibraryThing already does this with some of its Common Knowledge data, which is clearly established as important information to the user group the site serves. As an arts librarian, I’d love to see development in the physical description areas, since our patrons seem to be so influenced by the physical characteristics of our resources. I wonder if this could also be crowdsourced/added socially: in the same way that LibraryThing members contribute series and character information, perhaps arts library users could describe their resources in ways that they find important to them? And if each library added the data that was important to them, imagine how fleshed out, detailed, and useful our bibliographic records could be!

Every library is different, and one tiny 3 x 5 card can’t hope to fit all the information needed by all of the different libraries out there. So now it’s my turn to hold up a book and ask which components might be important. Think about your library, its users, and its collection. Pretend catalog cards never existed. Tell me: How would you organize your library’s materials? What information would you record?

* I don’t begrudge the instructor for his answer–it was correct in context in that ‘color’ isn’t included in the traditional 8 areas of bibliographic description, which was, after all, what the lesson was about. He is actually a fantastic instructor who I would recommend to anyone, and I’m totally going to steal that exercise idea someday when I’m teaching cataloging.

Another one of my co-workers spotted this in the January issue of Martha Stewart Living magazine. Note that the owner-and-color-classifier of these books is an interior designer. One of our majors is interior design. Coincidence? I think not.

Another one of my co-workers spotted this in the January issue of Martha Stewart Living magazine. Note that the owner-and-color-classifier of these books is an interior designer. One of our majors is interior design. Coincidence? I think not.