2 days. 2 staff. 1200 DVDs. One mission:

It may sound like a bad action movie tagline, but it’s true: two people reclassified our feature film collection in two days.

I say this because I get a lot of balk whenever I bring up reclassification, anything from upgrading to the latest DDC edition to instituting an entirely new schema. Libraries are understaffed, underfunded, don’t have the manpower or the time to go back and retroactively convert or upgrade or migrate to a new system. And I say (pardon my French): bullsh*t.

I’m not denying that it’s a lot of work. It’s a crazy amount of work. What I am saying is: isn’t that work worth it? Obviously every project requires a calculation of return on investment, and sure, sometimes the amount of effort expanded won’t be worth it. But how can you calculate the returned value of patron service? Doesn’t improved findability for patrons (which in turn increases library usage and circulation) warrant a significant investment? And to anyone who claims otherwise, I ask that you re-examine the mission and purpose of libraries in general, because if you’re not willing to invest in patron service, then what exactly is your purpose?

To the catalogers who balk: I know we’re all swamped and underappreciated, and most libraries have backlogs enough to keep them occupied until the year 2063. (And I can rant about that for the same amount of time, but that’s a post for another day…) Cataloging new acquisitions and making them accessible is important–it’s personally my highest priority as well as being the highest priority in our cataloging policies here. But as high as it is, it’s not the only priority, just as bibliographic records are not the sole point of cataloging. As busy as we all are, I think there are ways to work on updating and/or reclassifying a collection so as to improve patron accessibility and experience. Here’s what we did:

- Tuesday morning, circa 9 a.m.: The audiovisuals specialist and I decide to reclassify the feature films. Okay, that’s kind of a lie. It was an idea we’d been talking about for a while, 2 quarters at least. Repeated observation and commentary from students and faculty led us to believe there was a great deal of difficulty finding feature film DVDs and videos, which up until now, had simply been shelved in DDC/Cutter order. All features were assigned 791.4372 + Cutter number; essentially all 1200+ commercial Hollywood movies were arranged in alphabetical order. Try to imagine walking into a Blockbuster Video arranged like that and trying to find a movie. I sure hope you know exactly what title you want to see, because if you’re in the mood for a light romantic comedy or a scary thriller, you’re SOL. Sure, we could have built out DDC numbers for the film genres based on the schedules under 791.436 + Table 3C, but honestly, that’s not only a lot of work, but how does that help our patrons? Maybe it lumps together like genres, sure. But by that point you have a number so long that it wraps around the spine of the DVD case, making it difficult to read as well as still being a number that patrons don’t identify with. Much easier to just divide into sections by name of genre and label accordingly. And that was what we decided to do, and Tuesday morning we looked at each other and decided that we’d dallied around long enough, and we were just gonna bite the bullet and do it.

- 9:30 am: The two of us brave immensely strong winds on our way to the nearly office supply store to purchase a package of labels for the project. Total cost =$12.99 + tax.

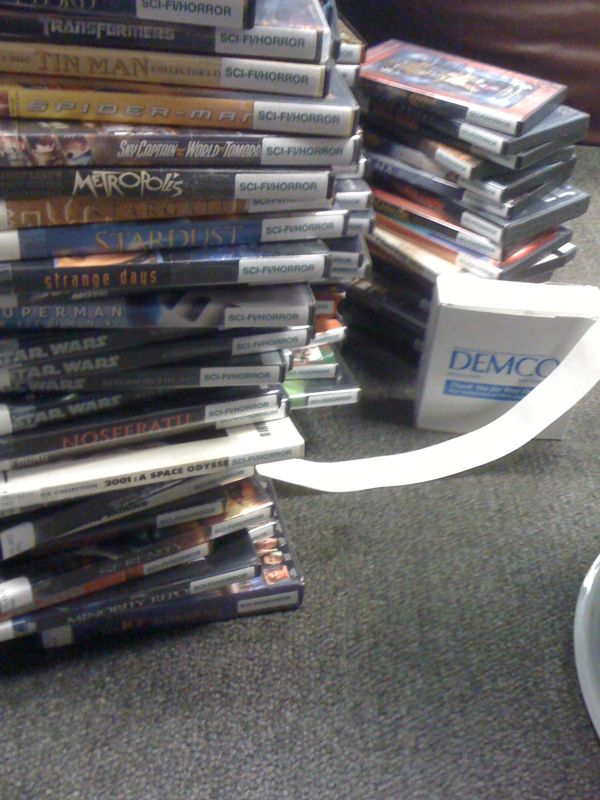

- 10am: We discuss and decide on 7 categories: Action, Animated, Comedy, Drama, Foreign, Musicals, and Sci-Fi/Horror. We debate other ideas, like Historical and Documentary, but we decide to keep it simple and just stick with the main seven. They are based on traditional movie genres as well as what our patrons commonly request, as well as what they don’t want–we’ve had numerous occurences of students checking out films only to return them with disappointment because they didn’t know the movie was a musical or in a foreign language. Separating those two categories out should help alleviate that problem, if not solve it entirely. We print color-coded labels for each section.

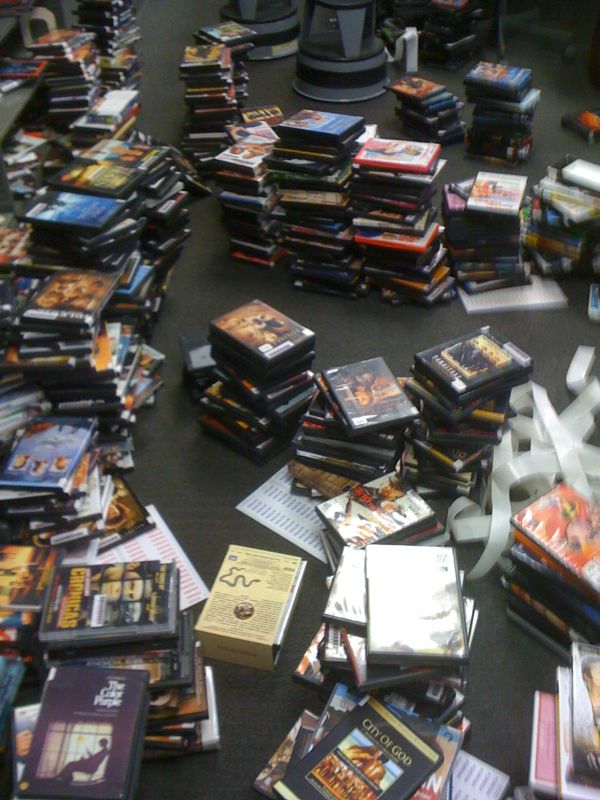

- 11am: We start pulling materials off the shelf and sorting them into piles. Of course we encounter problems as we go. Some movies span multiple categories; some are totally unfamiliar to us and we have no idea where to class them. We begin making executive decisions: all war movies will go in Action; all Jane Austen films will go under Comedy (where we have already decided to class romantic comedies); an animated film in a foreign language will go under foreign, because our students are more interested in avoiding subtitles than they are in finding (or avoiding) animated films. This is the thing about physical classification–there comes a point when these decisions have to be made. Yes, everything is miscellaneous, and I can point you at examples of animated foreign musicals. But you have to make a decision, you have to document that decision, and then you have to move on. And I think this is where many classification/reclassification projects shut down, either at this point, or even before, just from fear and anticipation of this point. (See: Open Shelves Classification.) Face it: you’re not going to please 100% of the people 100% of the time. There’s going to be a lot of compromise. Be Zen with the compromise. Embrace it. And most of all, be able to explain it to people–that’s one reason you’re documenting it, so you can say “here’s where we put war movies, we file them under action.” As long as you know where they go, you can direct a user there. Because believe me, someone, somewhere will be upset that you don’t have a top-level category for war movies. But if you can say, “hey, we didn’t have enough to make a separate section, but we put them all in action, you can find them all there,” as long as the person inquiring knows where to find them, they’re usually happy. (There are a few people who will never be happy no matter what. That’s life. Move on.) We end up with a small pile of materials that defy obvious classification, so we look them up on Amazon (notice I didn’t say the Library of Congress or in the bib record) to determine the best place for them.

- Noon-ish: Now that we have piles, we start slapping labels on materials. We take a few minutes to agree in which direction and where on the spine they should be adhered. Then we get to it, and madly begin sticking labels on everything, including ourselves.

- 1:00: Break for staff holiday potluck. Whee!

- 2:30: Back to work. The audiovisuals specialist continues to label while I begin changing call numbers in the ILS. Unfortunately, we don’t have any sort of batch change option, so each record must be changed individually. Previously, a DVD call number would read something like:

DVD 791.4372 AL42w

After the change, the call number now reads:

DVD Animated A

That’s a lot easier to read and understand, no?

We continue like this until the end of the day Tuesday and resume Wednesday morning. We get a little help finishing up the labeling from some wandering part-time staff in need of projects. After the labels are done in the morning, I continue to change call numbers in the system while the audiovisuals specialist begins shifting the stacks and alphabetizing and reshelving materials. After I finish working on the computer, I join her, and by 5 p.m. Wednesday, the project is done. Well, we still need to order some alphabet labels to replace the old DDC spine labels–until those arrive we’ll still alphabetize by the old Cutter number. But other than that…

So that wasn’t so hard, was it? Sure, it was a lot of work, but hey, that’s our job. I think it’s often fear and anticipation of the overwhelming nature of such projects that puts a stop to them even before they start. I’ve done quite a bit of reclassification now, and here’s some stuff I’ve learned so far:

1. Start small. Work in sections. If you look at reclassifying your whole collection, it’s going to be too much. This time around, we didn’t even do all of our audiovisual collection–we limited it to just feature films. When I updated our collection from DDC21 to 22, I worked section by section, first tackling 745, then 747. Break it down into manageable chunks. We’re on the quarter system here, so I like to go quarter by quarter. One quarter I took on 750, reclassing painters by name rather than country origin (since it made more sense for our students that way). The next quarter I did the same thing for architects in 720. Also, if you’re working in a smaller section, it’s easy to throw up a ‘pardon our dust’ sign telling patrons that there’s work going on in that section and to ask staff for help if they need anything there. Also, a smaller section or sub-section can function as a test case, where you can observe patron reactions and adjust accordingly before moving on to larger projects. Maybe (for some unthinkably bizarre reason) our patrons will hate what we’ve done with the DVDs. It’s a small enough section and easy enough work to restore them to the original DDC order if desired.

2. Have a plan. As much as it seems like we jumped into the project on Tuesday, it really was a long time coming and part of a larger strategic goal. Even though we finalized the categories that morning, we had discussed them in-depth previously as part of a larger collection reorganization. Make sure what you’re doing is in line with the larger scope of the library and the collection as a whole. Having a plan assumes research regarding your library’s collection and users.

2a. Once you have a plan, get to work. Once everything is ready to go, go do it. Try to do it as quickly and efficiently as possible. Don’t plan reclassification for a time right before you’re going on vacation, or it’s finals week in the library, or other situations where you might be interrupted. I think drawing this type of project out or letting it linger in limbo doesn’t do staff or patrons any good. Hence tip #1 to start small. If all you can do is one shelf a month, then pick your shelf and get it done and just do that one shelf. But do it, rather than putting it off until you “have more time.” We’re never going to have more time. Libraries never do. If you’re going to do it, find a way to get it done, or don’t do it at all.

3. Take advantage of available resources. Part of the reason we could reclassify our feature films so quickly is because both of us were intimately familiar with our collection. I can reclassify DDC 22 because I know the system like the back of my hand. I can look at most materials that come into our library and classify them immediately, without even looking at the schedules. This means I can reclassify sections in a day that might take the staff at out other campuses a week or more. Harness these strengths. Use people on your staff (yourself or others) with expert knowledge. Can you do some sort of batch change or find-and-replace in your ILS? Use that to your advantage. Do you have volunteers, interns, student workers who need easy projects? Set them up labeling or shelving.

4. Don’t overthink it. You can easily get bogged down trying to accomodate every tiny little niche category and user. Yes, browseability is important, especially in an arts library like ours. But remember that you can’t please all the people all the time. Remember that there are alternate means of access, like the catalog. There are still ways to find all the films set in a certain time period, or all the Pierce Brosnan movies. Think of your classification as broad browsing categories, and leave the niche, faceted searching to the catalog. Many people will not understand this, and everyone will have opinions about classification categories. But remember: this is what you do as a cataloger. This is ostensibly your area of expertise. It’s our job to consider ideas and suggestions from users and staff alike, but it’s also our job to use advanced knowledge to screen the ideas and create something functional, rather than getting bogged down trying to incorporate every idea and suggestion. There are other, better tools and technologies for that, and all these things can be designed to work together rather than replace each other.

5. Don’t get too carried away! I love classification and reclassification, and goodness knows I might reclassify everything in sight if given the chance. But some materials and collections don’t need it, and it’s better to direct energies elsewhere. Change for improvement is good. Change simply for change’s sake is just change. And change can be hard to adjust to, for library staff and patrons alike, even if it is designed to improve user experience. Which brings me to…

6. Documentation and training: Sure, some of the reclassification projects I’ve mentioned, like upgrading to DDC22, are theoretically pretty seamless to staff and all but invisible to patrons. Something like our DVD categories seems pretty self-explanatory. But believe you me, when we open our doors again on January 7, we’re gonna see some wide-eyed and confused faces. Be ready to explain–many, many times over–the new system and how it works. Make signs. Make handouts. We’re planning on typing up descriptions of the new categories, posting them in the audiovisuals area as well as on our student portal/website and faculty intranet. Additionally, I’ll be writing up something similar for internal library use, not just for staff reference but also training and succession planning. This way anyone who adds new feature films to the collection in the future will have documentation telling them exactly where to class Jane Austen or animated foreign films. This also ensures consistency, so that all war movies will really be classed under action.

7. (Most importantly) Have fun! Yes, this is a lot of work. Maybe I’m crazy, but I really enjoy these sorts of projects. I like classifying things, and I like having a tangibly demonstrable example of improving user experience. I can’t wait until the quarter starts to see the reaction from students and faculty. Maybe they’ll hate it and so we’ll change it. But maybe they’ll love it, and be very happy about it. That’s what I’m anticipating, and that’s what I’m looking forward to seeing–after the shock of change, the smiles on their faces, as they are not only happy with the new ability to find materials, but also the realization that we listened to what they had to say, and acted on it.